Extract:

Bertie Arrowsmith was still below retirement age, so I’d arranged to see him at the weekend. I’m never too keen on seeing the inside of my office on a Saturday, and chose to go to his home. The appointment was for eleven, and it was a few minutes before then that I pressed the buttons to the complicated entry system to the sixteen-storey tower block on the Southfields Estate where he and his wife lived. After several inept attempts which played havoc with my temper I finally succeeded in obtaining admission, and made my way up to the second floor, where I rang the doorbell to his flat.

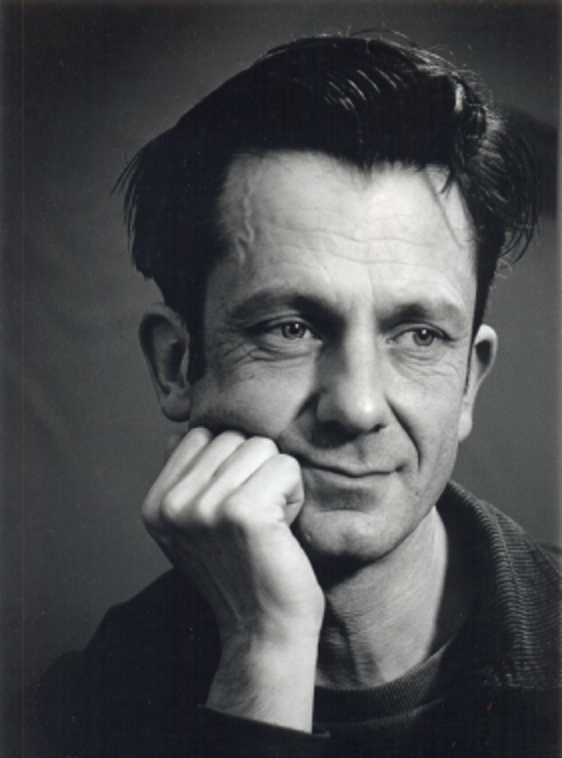

Bertie answered the door himself and ushered me into a homely little room with family photographs all over the place, and a table and bureau cluttered with papers. I was mildly surprised that he couldn’t afford anywhere better, then remembered that he and his wife had had to bring up three children on a single individual’s pay. The idea that both parties to a marriage have to work even when there are children is quite recent.

‘This is all going to be very difficult, I’m afraid,’ he said in his precise old-maidish manner, having conducted me to an armchair, pottered about, got me a cup of tea, and exchanged a bit of social chit-chat by way of introduction. ‘I’ve arranged for Emily to be out shopping. I want to save her embarrassment.

‘Anyway,’ he continued after further delay, and having sipped genteelly at his cup of tea, ‘I suppose I might as well get it over with. I’ve no doubt you’ve been told that Tamsin Defoe – a complete bitch, of course, everyone knows that – had been making snide remarks about my sexuality.’

I nodded. ‘So I’ve heard.’

‘I’ll admit that I’m not the most macho man you could ever wish to meet, but … Well, let me explain.’ He paused and looked miserable. ‘I’ve been happily married for over thirty years, and no man ever had a better wife. No-one could have supported me more loyally than Emily. She knows that I occasionally have – ah – difficulties in the sexual side of our marriage, but she’s been incredibly patient, and has never complained.’ He paused and clattered the spoon in his saucer clumsily before continuing. ‘Despite our having had three children, I think I’m rather undersexed, a rare complaint nowadays, or perhaps most people aren’t willing to admit to it.

‘But it hasn’t always been like that.’ He sighed shakily, the air expelled in nervous irregular breaths. ‘When I was a young man, nearly forty years now, I would sometimes’ – he cleared his throat – ‘feel a strong attraction towards members of my own sex. I gather that’s not unusual with teenagers, hormone imbalance and all that sort of thing, but with me it went a bit further. Maybe I was gay, I don’t know.

‘Anyway, while I was at Oxford I formed a relationship with another man. Or rather, youth. It wasn’t an offence even then; the law had been liberalized a few years before, but it still wasn’t the sort of thing you wanted to publicize, or at least I didn’t. Even nowadays I can’t understand those people who go about posturing and insisting on telling everyone they’re gay, and so on.

‘Well.’ He seemed somewhat at a loss. ‘Tamsin found out about it. And that’s why she started making my life a misery.’

‘Perhaps,’ I ventured, ‘she was just guessing.’

‘Based on my appearance and manner, you mean?’ Bertie gave a rather creaky little laugh. ‘I quite realize that no-one would be likely to mistake me for a former rugby league player. But, no. There was more to it than that. She’d come across some evidence. So if necessary she could have proved it.’

‘May I ask what the evidence was?’

Bertie pulled a wry face. ‘It was in the form of letters. I haven’t told you the full story, I’m afraid.’ He sighed again, more deeply this time. ‘The man in question was Marcus Defoe – her father. It was long before she was born, of course. We were both in our early twenties. Actually the affair wasn’t all that physical, apart from a bit of … well, I’m sure you can imagine. We exchanged some very foolish letters, full of classical allusions, comparing our relationship with those of the ancient Greek heroes and their armour-bearers, or the legend of Zeus and Ganymede, and so forth. Pretentious nonsense, I dare say. And yet’ – he blinked and swallowed before continuing uncertainly – ‘it meant something to us at the time, and even now, when I think about it … but it’s all water under the bridge, of course. Suffice it that after Marcus’ death, going through his papers, she found my letters. He’d kept them, all those years. And yes, if you’re going to ask, I’d kept his as well. Which I daresay makes us a pair of sentimental old fools, but there you are.’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t think so,’ I said seriously.

‘Really?’ He seemed almost childishly pleased. ‘I’m so glad to hear it. I’m afraid I’ve always imagined you as a straightforward sort of fellow with no time for sentimentality. Certainly not about a long-dead gay affair.’

‘You’d be surprised,’ I said with a smile.

‘I, er, hope you won’t find it necessary to … I’ve a feeling the police might be less understanding than you’ve been. Of course it’s not an offence any more, but no doubt they’d consider it all very ridiculous. I can just imagine myself being the butt of jokes in the police canteen. I wouldn’t be there to hear them, but even so it’s not something I’d care to think of.’

‘Of course I’ll treat it as confidential,’ I assured him. ‘Don’t worry about that. The only person I shall tell is Judy, and I assure you she can be relied upon. But I’m afraid I’d still like to hear what you were doing at the time Tamsin was killed. I’ve asked everyone else.’

‘Of course,’ he said, relieved at the change of subject. ‘I was in the first scene, but not the one in the herb garden. So I changed into military dress and made my way to the Killing Fields. I was there before anyone else, I think. On my own until Richard and Sylvia arrived.’ Bertie shrugged. ‘So I had plenty of spare time to return to the centre and kill Tamsin.’

‘A certain amount,’ I said. ‘But not plenty. Is that all you can tell me?’

‘I think so. Except that I must admit to being glad that Tamsin’s dead. I’m not proud of that fact, but I must be honest. If she’d lived, things would have become very … embarrassing for me. And what’s more important, for my wife and children.’

I finished my cup of tea and put it aside. ‘You’ve been very frank with me, Bertie,’ I said, standing. ‘And of course it hasn’t been easy for you. Thank you very much.’

‘It wasn’t quite so much of an ordeal as I’d feared,’ he said, showing me to the door. ‘As I say, you’ve been very understanding. And it’s a load off my mind. You … ah … don’t think I ought to tell the police?’

I thought a moment, then said, ‘No.’ I dare say I was wrong, but the police are apt to attach undue weight to things sometimes. Either that or ignore them altogether. And I had to admit that Bertie was probably right about the canteen.